Freedom of expression and access to information in Syria today

“All human beings by nature desire to know” Aristotle

Content

Introduction 1. Syrian Media before March 18th 2011 2. Alternative Syrian media: Renaissance of Freedom of Expression 3. Access to information in Syria before and after March 18th 2011 Libraries as keystone institutions for information access

Introduction

If we assume that people have a right to access information, this means that they should have access to institutions or techniques which provide access to that information. The right of access to information was established at the international level in 1946, when the UN General Assembly adopted, at its first session, resolution number 59 which states: “Freedom of access to information is a fundamental human right and the keystone of all freedoms declared by the United Nations”[1]. Information rights include the right to freedom of expression, access to information and the right to read.

For decades the Syrians were deprived of these rights and the access to information was very limited. Today, we are living a very delicate situation. A peaceful popular revolution transformed into a conflict between the regime forces and armed opposition. Since the 18 March 2011, everything has changed. Syrians began breaking the barrier of fear and started calling for their right to freedom of expression, one of the most important rights for which they revolted. Freedom of expression requires flexible access to a wealth of information. They have found their own ways to obtain this access and subsequently express their thoughts through alternative means such as social networks like Twitter and Skype as well as other technological means.

Keeping this pretext in mind, we will try to shed light on these issues in the most important kinds of institutions: traditional and new Syrian media and libraries.

1. Syrian Media before March 18th 2011

Since the Baath party first seized authority in the early sixties (1962), it realized the importance of the media and its potential to become a serious threat to its existence as a totalitarian ruling party. In the second statement it issued, the Baath party gave itself full power to seize all types of media, publishing and printing, public and private. According to this statement, the party also closed all newspapers and magazines issued before the 8 March 1963, including partisan newspapers, and kept only the official and party representative newspapers[2].

When Hafez Alassad seized power in 1970, printed media was condensed and represented in only three national newspapers (Baath, Teshreen and Althawra), severely limiting public opinion. These newspapers were structured in an institutional form. One of them (Baath) is under the authority of the national leadership and the two others follow the government directly; however, all of them were and still are dominated by the security control.

1.1. Law of Publications

After March 1962, printed press became frozen and the number of institutions controlled by the Baath party and executive authority increased. All these institutions followed the Only Media Directed (OMD) policy. Under the OMD policy, everything is under the control of the General Corporation for the Distribution of Publications. The GCDP prevents thousands of publications from circulating and rips thousands of magazine pages before distribution. Such was the case with AlNakked, AlDomarry and AlNahej magazines, to name a few.

According to the Law of Publications, every publication should be controlled directly by the Minister of Information and any breach of the authority principals could cause the cancelation of this publication, as has happened many times with multiple publications. Television and radio stations were not included in this Law of Publications, and are still exclusively under the total control of the government.

1.2. Law of Journalists’ Union

According to Article 3 of the law, which was issued in 1990, the Union of Journalists believes in nation goals and is committed to achieving these goals in accordance with the decisions of the Baath Party and its directions. Article 54 states that the union has the right to penalize any member who breaches the goals of the union, and no one in Syria can be a journalist without being a part of this union.

2. Alternative Syrian media: Renaissance of Freedom of Expression

From the first day of the popular revolution in Syria, the government occupied the space of the media and tried to distort the facts, while at the same time depriving people of delivering their voice to the world. International media was also forbidden to enter Syria and document what was happening in the country. Syrian activists recognized from the beginning the importance of the media. They learned from past experience and started to create for themselves an independent new media to be the alternative of the Syrian official media [3].

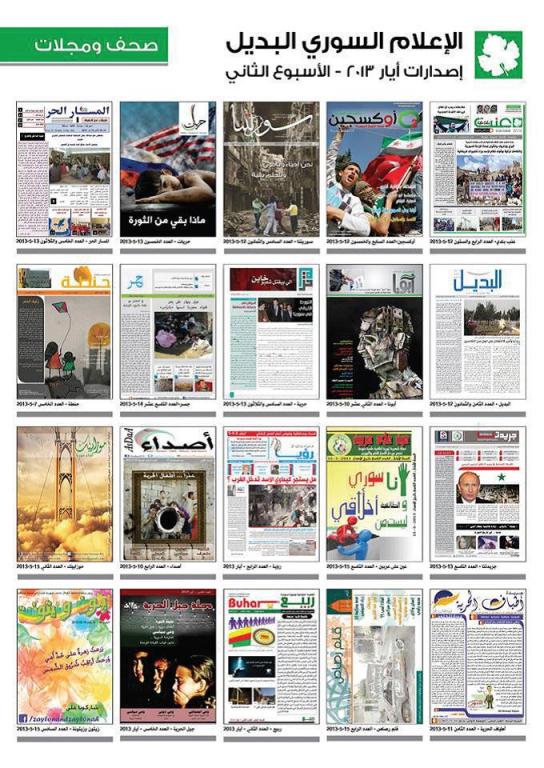

The alternative media created by Syrian activists expresses the popular vision, thoughts, and dreams of freedom and dignity in total liberty. In two years, 80 publications appeared in the form of magazines, newspapers and periodic bulletins. Some of these publications were stopped for financial reasons and others because of the situation on the ground and the obstacles of working within the escalating violence and lack of resources.

Most of these publications are still regional, with each one expressing and covering the local region where it was issued and distributed; however, some of them were able to be more widespread in their coverage, releasing articles to cover news throughout Syria and expressing the views of the majority of Syrians in several areas such as EnabBaladi, AlmassarAlhor, Dawdaa, and others.

Briefly, during the last two years, Syria has been seeing a remarkable development in print and audio-visual media. Several television and radio stations, magazines and newspapers have appeared and are still trying to deliver a clear picture of what is happening in the country without any restrictions, borders or pressure of any kind.

Figure1. Example of new printed and electronic media during the civil war in Syria (issues of May 2013)

3. Access to information in Syria before and after March 18th 2011

Indeed, according to the human rights organization Article 19 and the list of recommendations at the end of its report entitled, “Global Trends on the Right to Information”, governments, civil society, and businesses are essentially expected to ensure the access to information in any country as summed up in the following brief points[4]:

- Governments ought to “develop and support appropriate systems for the dissemination of information to all members of society, taking into account culture, education, wealth and other differences.”

- Civil Society ought to “develop and apply innovative and effective methods of producing, accessing, disseminating and using information.”

- Businesses ought to “contribute actively, including through technical and economic support, to establishing better systems for information generation, storage and dissemination.”

As we discussed above, access to information in Syria was very limited. When applying the above points to the case of Syria, it becomes evident that none of them are visible. The Syrian government develops and supports systems that fit or are in line with its political orientation and objectives, especially at the domestic, political level, without taking into consideration differences in cultural beliefs and education.

Civil society is a strange concept in Syria; civil associations are not allowed, with the exception of those founded by the government or following a political decision. All of these associations, including the Syrian Libraries Association, are controlled and unable to make independent decisions. The fact that none of the professional librarians were involved or part of this association further illustrates this.

All businesses in Syria focused on commercial aspects and financial investments. Access to information was not a priority for these kinds of projects, especially in such a controlled environment.

3.1. General Syrian Corporation for the Distribution of Publications

Founded in 1975, the GSCDP’s mission is to carry out prior censorship on all publications distributed in Syria such as newspapers, magazines and books. According to the law of its foundation, it is the only institution authorized to distribute publications in Syria and the Board of Directors should be composed of officials from the Ministry of Information, the army and the Baath Party. The GSCDP, according to this law, has the right to control and refuse the distribution of any publication. It has the right also to determine the amount of distributed publications without referring to the publisher or distributor. So within its authorities, and as we mentioned above, for a long time the GSCDP banned thousands of books from entering Syria, and tore pages of thousands of publications before distribution[5].

3.2. Access to information today

During the last two years, the only way for Syrians to get information has been through the Internet- particularly social networks. They have been able to develop a very wide communication network, thousands of Facebook pages and thousands of accounts on Twitter and Skype. Many digital projects were developed by Syrians, both inside and outside the country, to ensure access to information for all members of the society. Televisions (Syrian Revolution TV, Syria Alshabab Channel, Alghad TV, etc.), radio stations (RadionAlkul, Hawa FM, radio Smart, etc.), and all kinds of publications appeared online, especially outside the country. Today, information is available for all Syrians, but this availability of information for those who are still in Syria is dependent on the availability of electricity and (naturally) the Internet. Many associations representative of the Syrian civil society were founded during these two years, inside and outside of the country.

Libraries as keystone institutions for information access

As librarians, we believe that libraries can serve as a cornerstone institution that can ensure the individual’s right to access information and can further the promotion of the commitment to human rights more generally.

The main mission of any library is to provide people with information, which they otherwise would not be able to access. Libraries should also be concerned to collect, in addition to works of literature and accessible reading materials, works that address basic information needs relative to the context. Libraries may serve as places where public and governmental information may be archived and organized; help promote literacy by giving people access to books and encourage a literate culture; and promote digital literacy by providing access to computers and other information technologies.

In Syria, because of the local laws relative to publications (as mentioned above), all these tasks were done but with very limited access. The Syrian Library Association was founded on a political decision, it does not contain any professional librarian and today all of its activities are frozen because of the situation.

Libraries were also affected by the war situation: access to the libraries became very hard with the army on the ground, and in addition to daily bombardment, explosions, suicide attacks, etc., some libraries have also been bombed like the libraries at Aleppo University, AlBaath University in Homs and Damascus University. Thus, due to this situation, students and employees have been deprived of access the libraries. Due to its widespread availability, the Internet remains today the only way to access information in Syria.

- [1] United Nations. 1948. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/history.shtml

- [2] Alsafady, Motaa. 1964. Baath Party: The tragedy of birth and the tragedy of the end. Beirut, Dar Alaadab.

- [3] Figure number 1. Example of new printed and electronic media during the civil war in Syria (issues of May 2013)

- [4] Human Rights Organization, July 2001. Global Trends on the Right to Information: A survey of South Asia. Chapter 5- Recommendations.

- [5] Albonny, Anwar. 2004. Legal mechanism of the dominance of Baath Party in Syria. AlhewarAlmotammaden, N. 989. 17/10/2004. http://www.ahewar.org/debat/show.art.asp?aid=25146[Accessed 14/07/2013]